My final exams are nearly always grand sociological experiments that don't accomplish what they're intended to. Take last year, when I taught a composition course centered on robots. The object of the course, other than getting better at writing analytical and research-based papers, was to think about how deep the differences between human thought and artificial thought really went and to examine the reasons (and create better ones) for why robotic life is different than human life. So, their job was to, with their new powers of analysis, trouble ideas about human supremacy (We're better than robots because we have organs? Really? What of people with mechanical arms, legs, etc.?) and come up with new, more logically sound ideas about what, if anything, actually separates human life from created life.

So their final exam, I thought, was bound to be a fun one. We had just finished watching Bladerunner, and so I asked them to make their own Voight-Kampff test for differentiating humans from robots. In order to do so, obviously, they had to choose an aspect of human life that they felt was pretty demonstrably and reliably different from imitated life (as the Voight-Kampff attempts to do, relying on empathy). They were asked to write me a cover letter explaining why they chose the one aspect of human behavior that they did--how they reasoned through it and why they believed it could not be imitated. Many chose effective markers of behavior (compassion, humor, memory), but the great majority did not explain in a particularly convincing way how reliable that marker was as the basis for a test, and their tests themselves, for the most part, did not really live up to the consistency and rigor of even the Voight-Kampff, which is itself brought into question in the book and film. I expected this to an extent--I even had a brief essay exam the day of the final that asked them to justify, if they could, using their test to determine the life or death of an entity who might be human, and most said no. But I did want rigor, and I did want their tests to be an exercise in self-assessment--holding themselves up to a mirror and asking questions about how we "earn" the special rank of humans, how we demonstrate humanity or fail to demonstrate humanity in our behaviors.

Now, there was lots I could have done to improve those outcomes. I probably neglected to discuss with them the basics of test construction and concepts like reliability and validity. I've always kind of had a knack for constructing good tests, and it speaks to why I'm good at taking them--but of course everyone has not had the experience of gaming out a test, and many people have always seen tests as arbitrary and random. Sometimes they're right. So I definitely needed to explain the purpose and methodology of testing more, and to command a certain degree of rigor up front.

But there's another problem, a sociological problem, I've learned, with asking many people to conduct an assessment based on their own critieria. The problem is that they tend to choose criteria that they themselves can regularly live up to. But assessment should have a high performance end and a low performance end--when asked what one needs to do to be good at something one wants to be good at, to qualify as something one wants to be, most people tend to set the bar where they can consistently reach it. Thus they're pretty much always guaranteed to succeed, to fall in the "above average" category. It's the same logic that explains why students regularly rate their performance at about a B if asked--the idea is that pretty much anyone can be above average if they show up, do some things. The same was true of self-assessment in the case of this final exam; I asked them to examine what was required of humans to qualify as humans, and they answered, "We have to qualify?"

Naturally, it's uncomfortable to examine whether you qualify for something you considered a given. It's upsetting to consider that you may lose what you thought you always were if you fail to perform it.

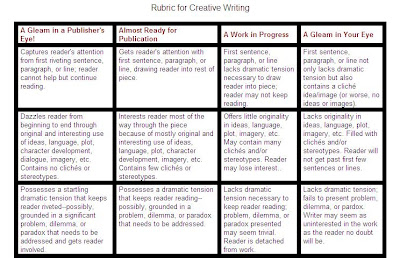

But I couldn't help it; I think assessment is awesome and necessary, and I had a fantastic creative writing class this semester, so I decided to try it again. I asked them to create a self-assessment rubric for their writing, based on criteria that they thought would best measure the success or failure of their writing--so, this was not a rubric designed to fit all writing (as were some of the ones I showed them as examples, above), but one designed to help them evaluate whether they'd done the job with writing that they wanted to do. And I did the cover letter thing again, asking them to explain what they saw as their ultimate goal for their writing, what elements they privileged in their writing that would help them reach that goal, and what kind of audience they imagined for that kind of writing. I explicitly left room for them to go big or small with their writing goals--for them to aim their writing mainly toward their moms or themselves, or for them to write for a vast (paying) public. I wanted to make it clear that I didn't expect them all to go on and get MFAs or to all try for the big publishers. I wanted them to be realistic and also to think of what exactly they enjoyed about writing, and what the greatest fruition of that enjoyment would look like.

Then they designed rubrics that detailed what major elements they were shooting for and what their writing would look like at various levels of achieving that element. So, many chose elements like character, plot, and voice, but they also came up with others more specific to their goals: "ideas" for a writer who prioritized fiction that could change people's outlooks and improve social conditions, "shock" for a guy head over heels for Chuck Palahniuk, "message" for a Roman Catholic writer wanting to write interesting fiction for (but not necessarily about) Christians. All had particular goals in addition to more traditional aims, and talked about those goals specifically and well.

I've asked them for permission to post some of their rubrics here, and when I get the electronic copies back from them, I'll make another post looking at how they constructed their rubrics specifically for their own writing as well as how those rubrics could be widely applied.

No comments:

Post a Comment